Welcome to the book review site where statistics meet everyday life in the form of words and phrases. If you love to crunch numbers and read great narratives about human stories, we’ve got the content you need to make life better.

Our story begins in the same way you probably found the site, with a need to find out more about numbers, technology, and the books written about them. We discovered a lack of information online, so we decided that the time was right to create something that other people could find and read.

How We Choose and Review Books with Care

We carry out extensive research on the books we plan to review, ensuring that we only choose titles that match our interest in numbers and narratives. This means that you can be sure you’ll get to read a review on a book that has a good chance of catching your attention.

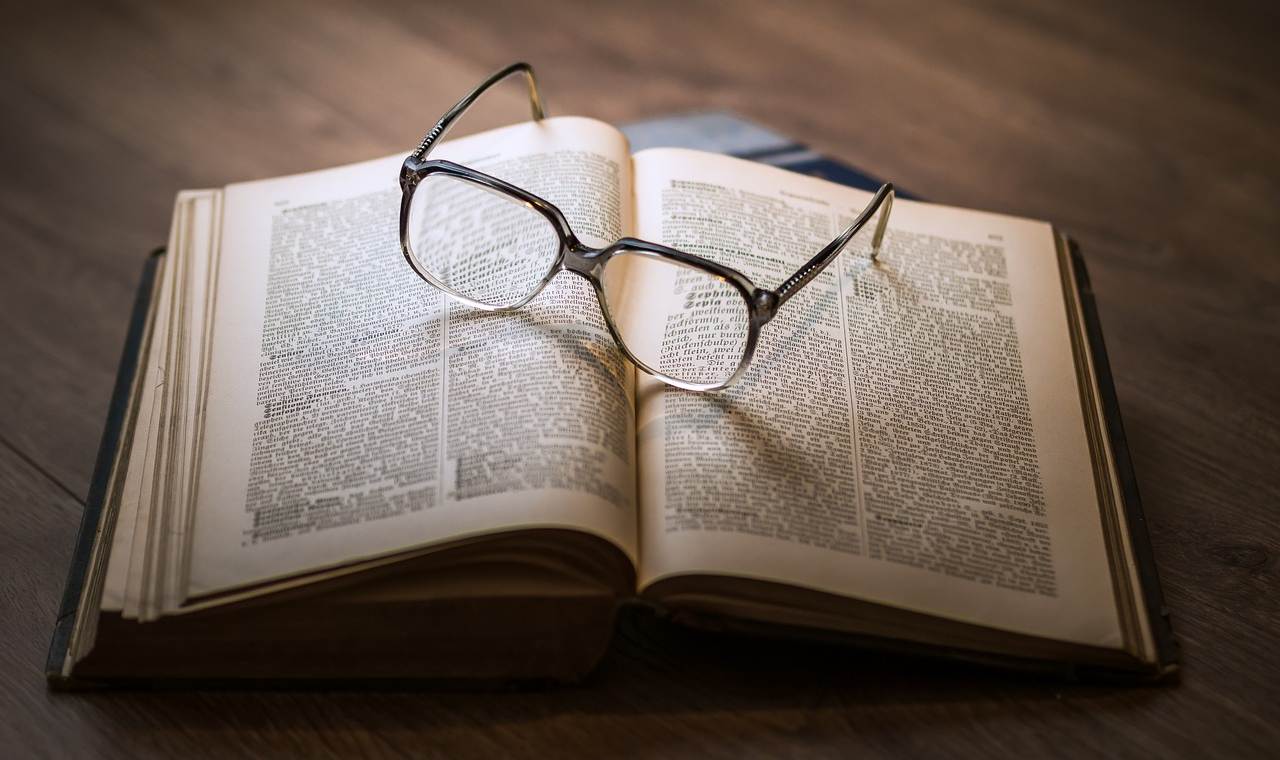

Once we’ve decided which books to focus on, the next step is to read, of course. Our selection process naturally throws up some books we’ve already read as well as new ones that we haven’t. Regardless of whether it’s new to us or not, we read it from cover to cover to see what it’s all about. As any book lover will know, this is a huge pleasure and not something to be rushed.

If it’s a new book, we want to get a review up quickly to help anyone who is looking for useful information before deciding whether to read it or buy it. However, we avoid rushing our reviews as this can lead to them being poorly written or missing out on important details.

Rather than focusing on the dry aspects of any book, we always look deeper to see what human elements it contains or how it has been brought to life in other ways. This isn’t always immediately obvious but we think it’s well worth taking the time to consider this side of the story and what it teaches us about the world or human nature.

How We Turn Reading into Insightful Reviews

Once we’ve seen what the book offers and reflected on its main messages, we’re ready to start the writing process. This is where we get the chance to be creative and find the best way to explain it to you. We don’t impose a fixed format on our reviews because each book is different. Sometimes, we think of new or unique ways to present the information that helps to make it more of a memorable review for our readers.

Like the process of reading and understanding what the book is about, writing the reviews is an enjoyable process that shouldn’t be rushed. Rather than simply telling you what the book is about, we always go the extra mile to make the reviews interesting to read and add greater depth.

If there’s a deeper story buried behind the main theme or a fresh way of looking at the world to be discovered, this is where we can lay it out for you. We don’t like to compare one book to another, but sometimes the comparisons are so important or obvious that we feel there’s no option but to mention a book that’s somehow related to the one we’re reviewing.

How Numbers Shape the Stories We Love

Why do numbers matter in storytelling? Because they shape the world we live in. Whether it’s data-driven decision-making, statistical insights into human behavior, or groundbreaking innovations in AI, books that blend math with real-world impact give us a deeper understanding of our surroundings.

Some of our favorite topics include:

Big Data & AI – Books that explore how data is reshaping industries, from finance to healthcare.

Statistical Thinking – How numbers influence everything from sports to politics.

Mathematical Biographies – The lives of great thinkers who shaped our understanding of numbers.

Tech & Innovation – The role of algorithms, cryptography, and coding in modern society.

Decision Science – How probability and statistics influence the choices we make daily.

If these themes interest you, you’ll love our reviews.

Tell Us What You Think

We’d love to hear what you think about our book reviews. After all, we write them to help you decide which books to read and to enjoy them even more. If you’ve discovered a fantastic book thanks to our reviews or want to point out what you think we could do better, we’d love to hear from you.

Every book review is based on our opinion and we know that not everyone is going to agree with it. Healthy discussion around the merits of a book and its real meaning is to be encouraged, as it can help everyone involved view it differently.

Books That Bring Math and Tech to Life

The books we review are highly varied, but all have a tech or math angle that hooks us. It might be a human story about people working in the math and data world, or it could be a tech-focused tale about computers and hard drives. We don’t mind as long as it meets our criteria for numbers and literature.

We like to think that all our efforts help to make this the best book review site around and perhaps the only one you’ll ever need to use. Yet, we’re aware that there are plenty of other people out there reading the same books and writing reviews.

With our team’s excellent backgrounds in numbers and literature, we feel confident that our reviews will give you fresh insights into the books we’ve read and reviewed. We enjoy creating these reviews and we hope you enjoy reading them just as much.